On fiction genres and the elements that power them: Part 2

Photo by Hudson Hintze on Unsplash

Last week, we unpacked the idea of genres, tropes and the storytelling elements of fiction. Then we discussed how those function within five genres of fiction. This week, we pick up where we left off and engage with five more genres, as well as dive into subgenres, cross-genre and multi-genre works.

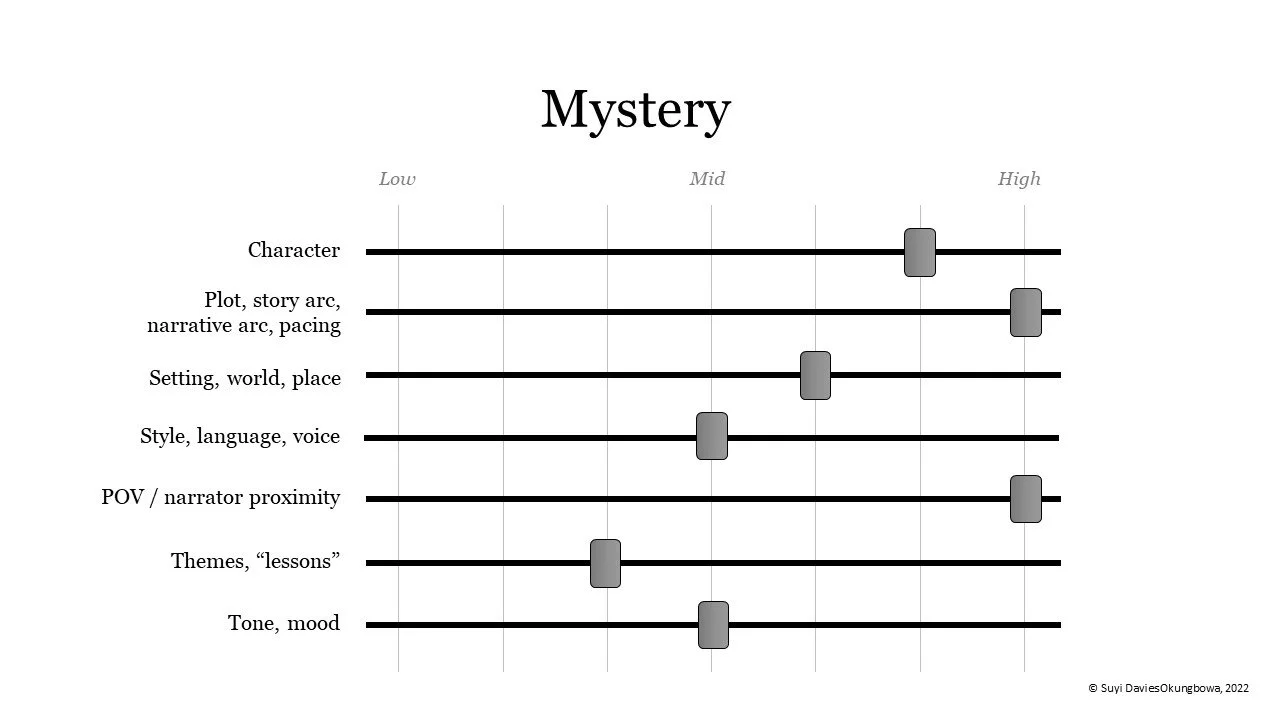

6. Mystery

The driving force of Mysteries is inquiry. A bunch of questions and the search for answers. Whodunnit? Whydunnit? Howdunnit? At the core of these questions are often multiple characters, the most prominent of whom include those doing the asking, those of whom the questions are being asked, and a surrounding cast of other persons of interest. The narrative then privileges the search for these answers and which of these characters may offer the most insight in leading us there. This makes character and plot/story arc—as well as pacing—crucial to how Mysteries unfold.

We’ll also see here that POV is crucial, as part of the deft handling of mystery storytelling is the withholding of information, which is often done by limiting the reader/audience’s impressions and inferences to those of a character or two. Place, once again, tends to play a part in confining the space within which we attempt to answer these questions—it’s why locked-room mysteries (Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle) and small-town/limited space mysteries (Gillian Flynn, Shutter Island, abandoned spaceships) are so popular. Outside of these, most other elements can go either way, depending on authorial choices. Recent authors I’ve read whose approaches fit this bill (and whose work I enjoy): Parker Bilal, Attica Locke, Kwei Quartey, Tetsuya Honda, Tade Thompson.

7. Crime/Noir

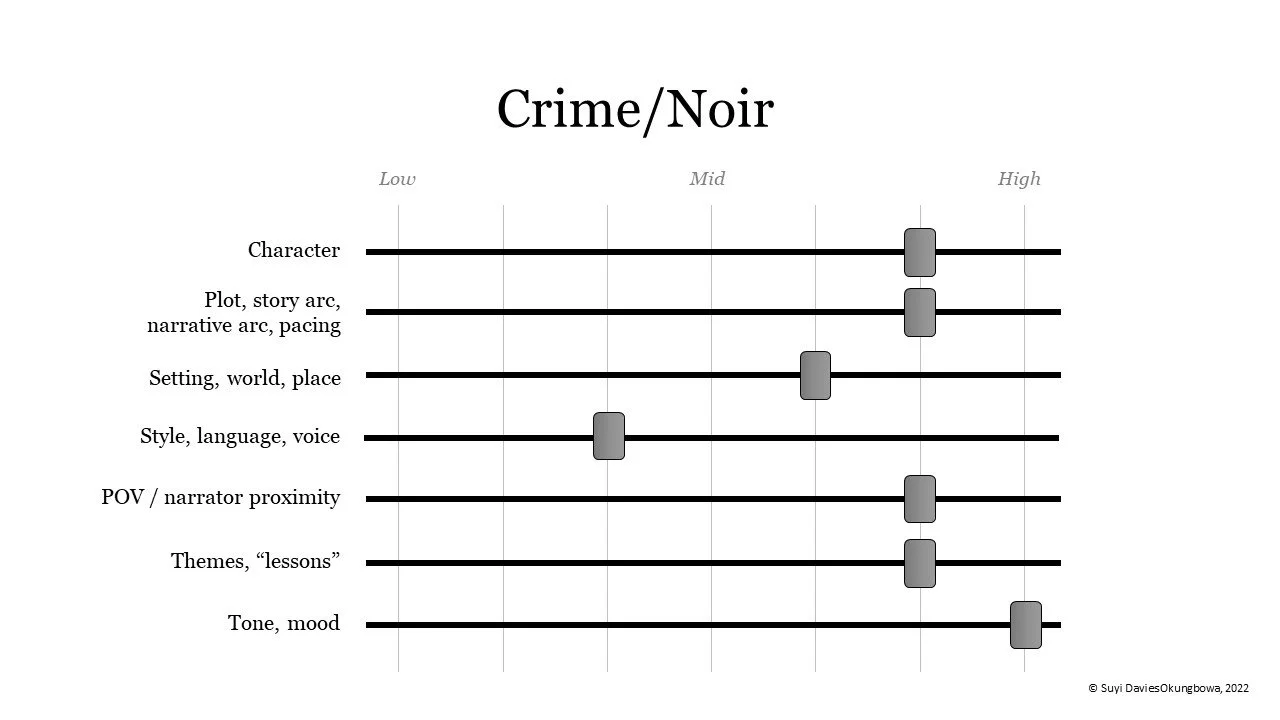

Most folks will be surprised that I separated this from Mystery and Thriller (or even Suspense), but even though these genres often find ways to go hand-in-hand, they in fact focus on different things. As I discussed above, Thrillers focus on invoking thrills, while Mysteries focus on answering pressing questions. Crime is more nebulous: it focuses on morality, and the seemingly inescapable moral grayness of the human condition. This is why Crime stories tend to be more introspective and moody. In fact, I’d go out on a limb here and say that what we call Noir is the audiovisual representation of this brooding mood/tone. Based on this, then, we can say that Crime requires a heightened mood and/or tone, with a tight focus on character actions and consequences (and how that drives, alters or affects the course of the narrative/story arc).

Two other elements that tend to be heightened here include the themes & “lessons” (which can be anything from “Crime does not pay” to “Crime does pay”) and how close we’re allowed to get to (and root for) key characters. It’s why we can be intrigued by the horrible people and their horrible actions in The Godfather or Breaking Bad or Fargo or The Wire: we get them, even if we’d never do what they do. Place, as with Mysteries and Thrillers, also tends to play a key role. And lastly, style/language/voice can go either way, depending on the author.

8. Comedy

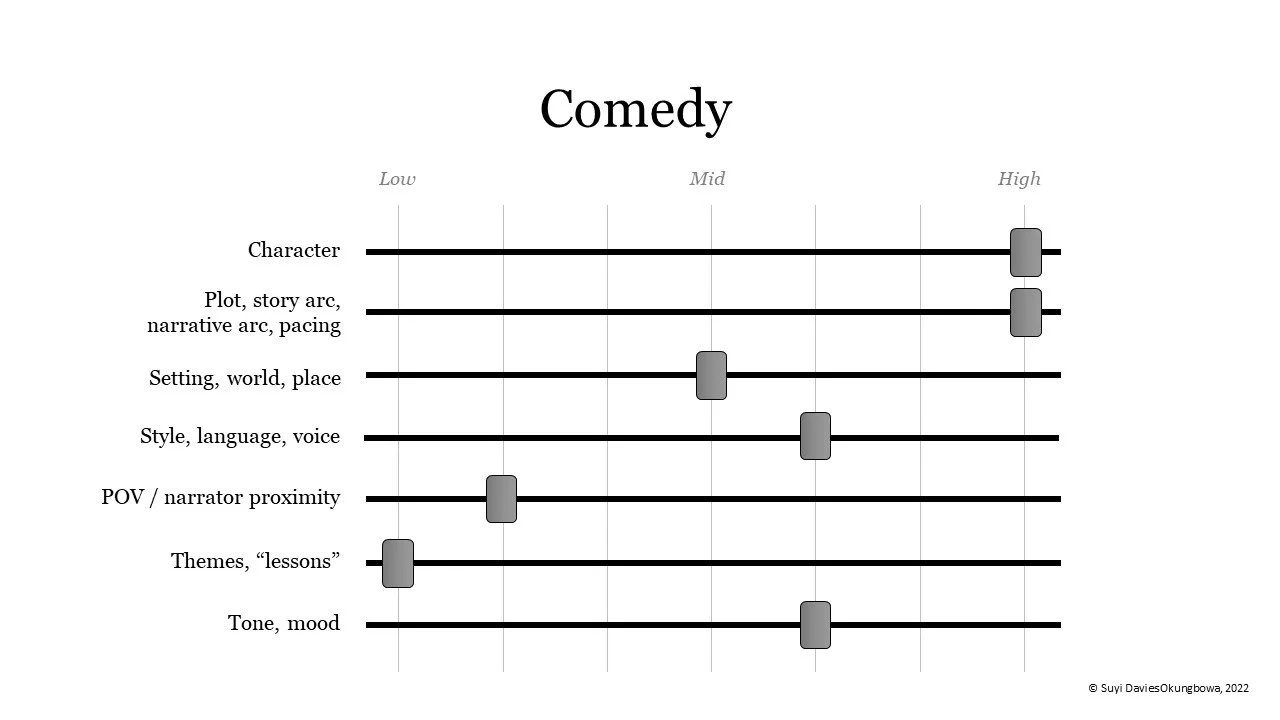

Contrary to common thought, the goal of comedy is not simply to generate humor and/or make us laugh. Aside from invoking amusement, comedy also provides entertainment and delivers spectacle. Therefore a major part of comedy is in the performance, even within the written word. Character actions, not just the why but the how, are key. Also key is the timing of beats, actions, punchlines—these are functions of time and pacing, and therefore functions of narrative. In this way, the two biggest drivers of comedy are not just the smart stuff that’s being said in dialogue and narration, but the character performance and narrative delivery.

Also key to comedy is often the voice/language used, as well as the tone & mood employed. This means comedy can be fluffy and funny (Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series, Friends, half of all middle-grade novels) or dark-ish and funny (The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy, Our Flag Means Death, the other half of all middle-grade novels). What comedy doesn’t always need to rely on is limiting a reader/audience to a particular point-of-view (because we need to be a degree removed and “in on the joke” to get it) or attempts to moralize (which are rare). Setting/place can move in either direction.

9. Historical

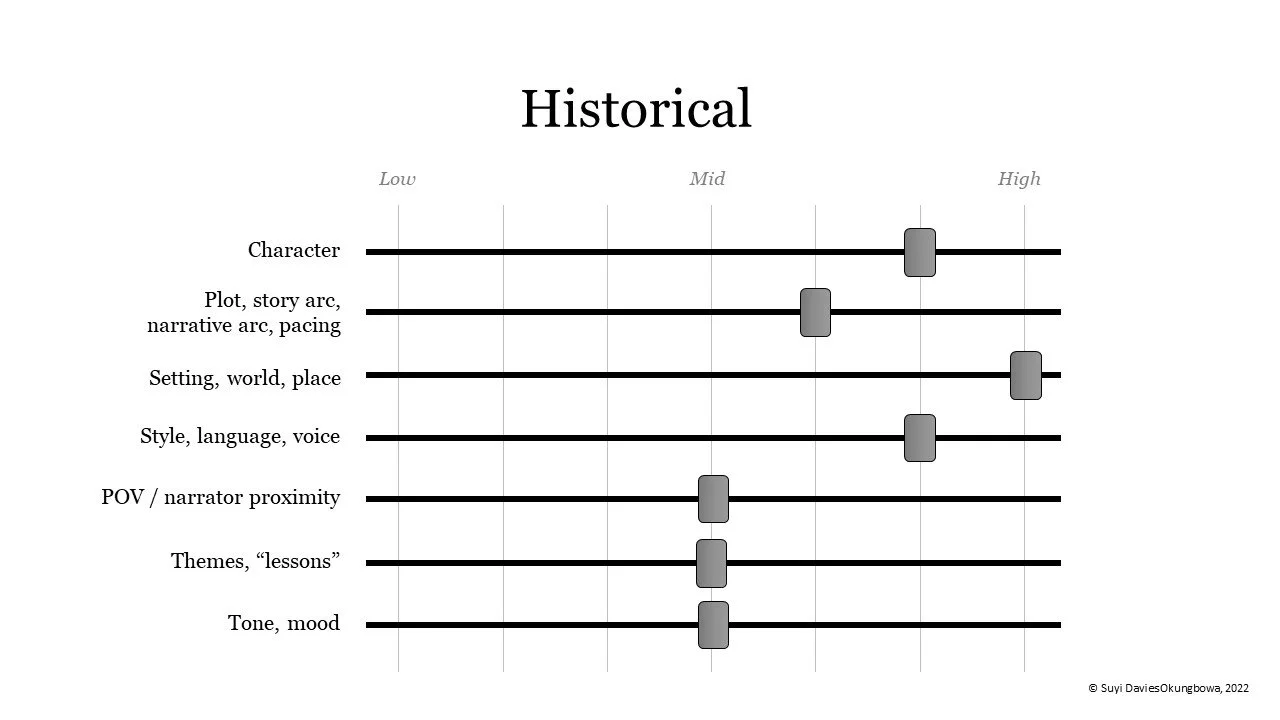

This is very similar to Science Fiction and Fantasy, in that it is strongly Place-driven (though not as often idea-driven as SFF). Where it significantly differs, though, is in the style/language/voice element, which for SFF could go either way, but Historical stories rooted in a particular (and real) time and place must reflect the sensibilities of said time and place (which sometimes, could also include tone & mood).

Other elements remain the same as for SFF, save for a slight diminishing in plot/narrative arc, as there isn’t always as strong an expectation for Historical works to lurch forward at a pace deemed “exciting.” More often than not, Historicals are allowed to move at walking pace and be more contemplative. We don’t have the same pacing expectations for Beloved as we do for the novels of The Expanse, just like we don’t watch Downton Abbey for the race-to-the-finish thrills of Stranger Things.

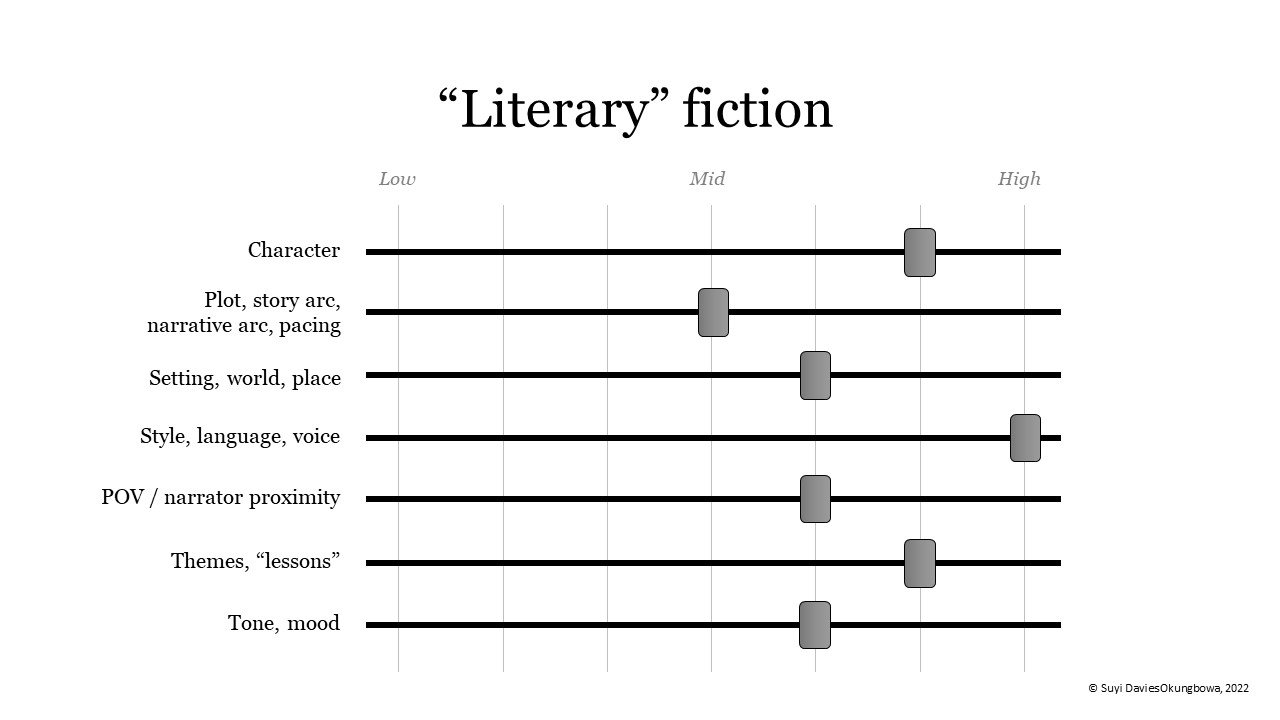

10. “Literary” fiction

I left this for last because it is yet another genre I do not quite consider a genre per se. Just like Suspense and Horror are reflections of mood & tone, what we have come to understand as “literary fiction” (or mainstream or realist literature, or whatever else it’s called out there) is simply fiction that employs style/language/voice as a primary driver over other elements. Character and themes tend to be two other heightened elements, but plot/narrative arc often tends to be either diminished or mostly employed as a structuring element.

Pretty much any element outside those three may move in either direction, but most tend to be slightly heightened to buttress certain strengths of the work. A place-driven work, for instance, will likely also heighten mood & tone in order to sharpen the reader’s experience (Elena Ferrante’s work does this splendidly, something that’s even more so captured in their film/TV adaptations). Likewise, voice-driven work with a first-person narrator will require heightened POV leanings. Et cetera, et cetera.

Subgenres, multigenre, cross-genre and hybrid genres

Now that we’ve seen how this plays out in various genres, let’s consider how this approach works when we go beneath the genre to a specific subgenre under the same umbrella. We’ll do it with the first—Science Fiction and Fantasy—and with my first two novels, David Mogo, Godhunter and Son of the Storm.

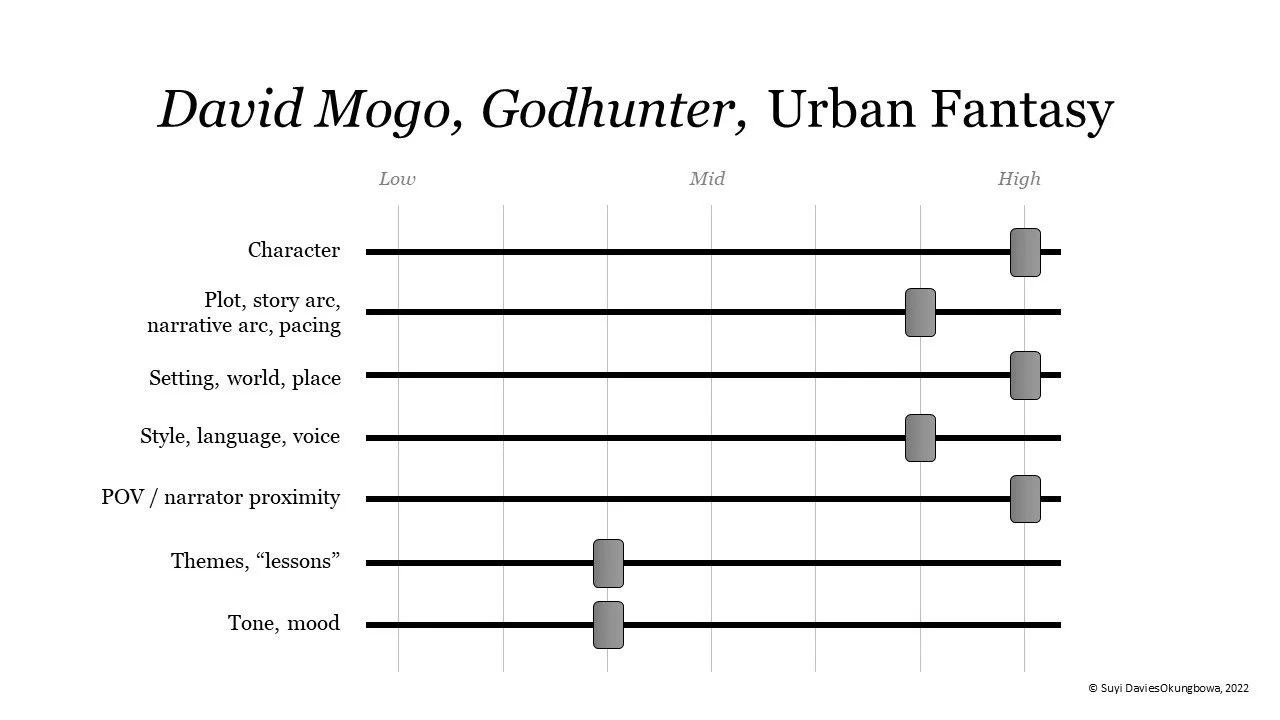

David Mogo, Godhunter has been called many things. Godpunk, contemporary fantasy, mythological fantasy, etc, but what it’s most identified as, I think, is urban fantasy. Urban fantasy, in my understanding, is a specific strain of SF&F that carries the audience expectation of a story world built within a contemporary city of sorts, with certain non-human beings (werewolves, vampires, monsters, gods, etc), conflicts that rub a normal world against a different one (hidden or unhidden), and a tone & mood that leans dark-ish. Knowing this, here’s what I think David Mogo, Godhunter looks like slider-wise, lending some insight into what the general representation of urban fantasy might look like.

We can see that Place remains strong. However, David Mogo is very voice and POV driven, with David’s first-person narration front-and-center, so we see style/language/voice and POV/narrator proximity shoot forward.

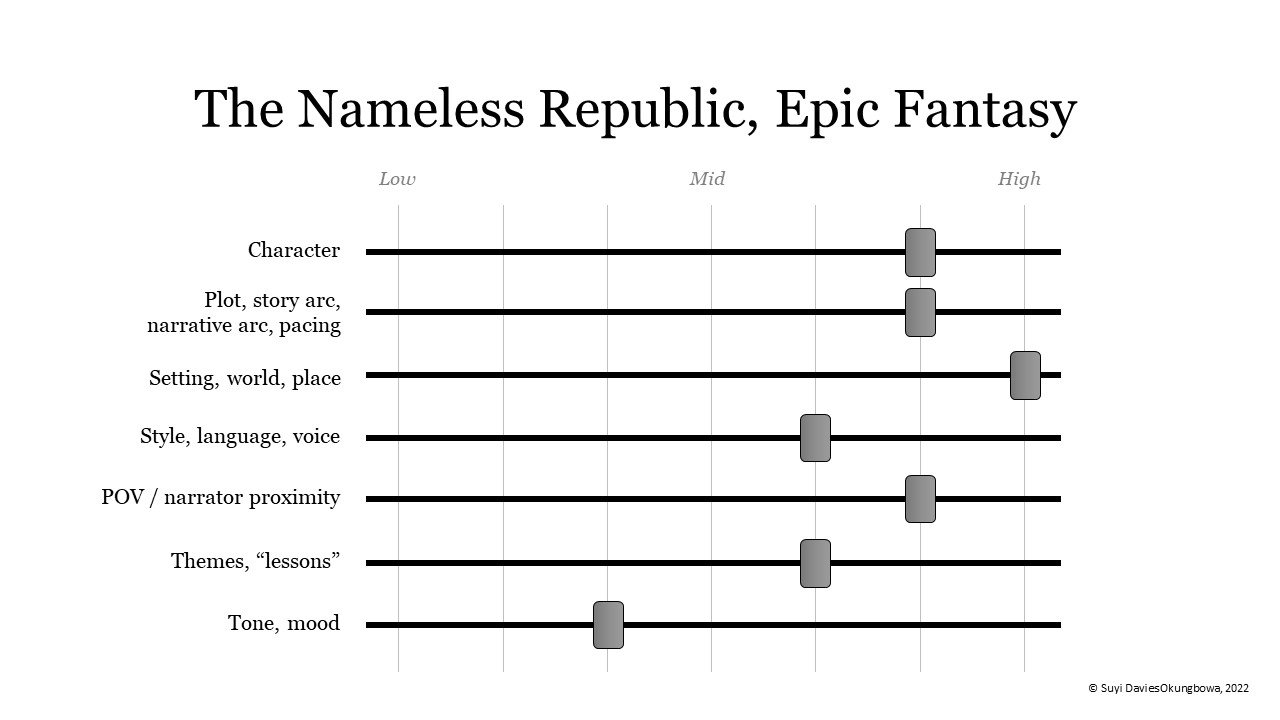

With Son of the Storm and The Nameless Republic trilogy, which is epic fantasy—i.e. sagas that span large expanses of time and/or space, often taking place in a secondary world (i.e. not earth as we know it) and often involving ultranatural powers akin to magic—the sliders look a little different.

You can see character, POV/narrator proximity and voice are scaled back a pinch because the fate of the world/place is heightened a bit more in this subgenre, and the characters are all players in a game much larger than their individual selves.

Now, what about when we cross genres, or when genres are mixed or layered one over the other? Well, we see genres complexified when combined to produce, say, a sci-fi mystery or literary horror, with the author asking themselves what kind of story they want to tell and then deciding what needs to be present to tell that story. Intertwining the dispositions of these genres produce interesting results, with certain elements that ordinarily wouldn’t be heightened in one genre suddenly getting a boost due to crossing or hybridity with another genre.

Here are some of my interpretations for a couple of books I’ve read in the recent past:

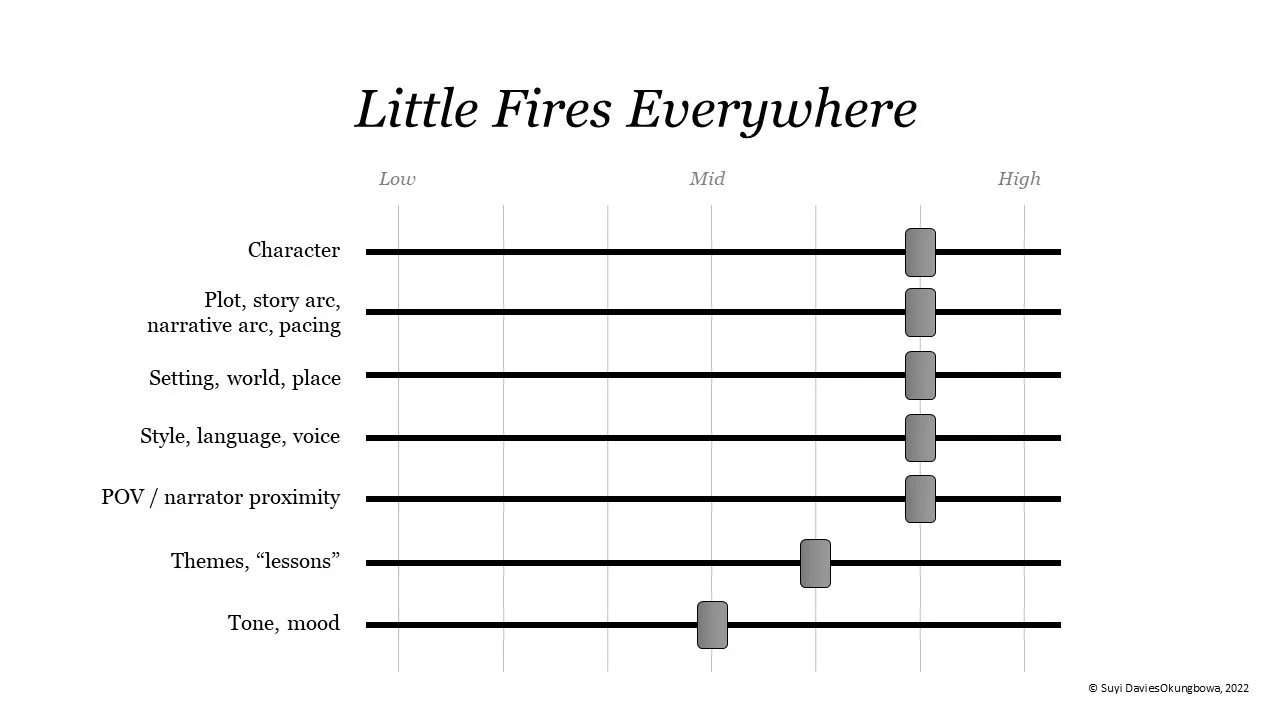

Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng, Upmarket Fiction

Think of “upmarket” (also known as “book club fiction”) as the publishing industry’s way of saying a story carries the dominant sensibilities of a “literary” novel, but injects the pacing and narrative approach of more traditional “genre” novels, say, a thriller or mystery or romance, etc.

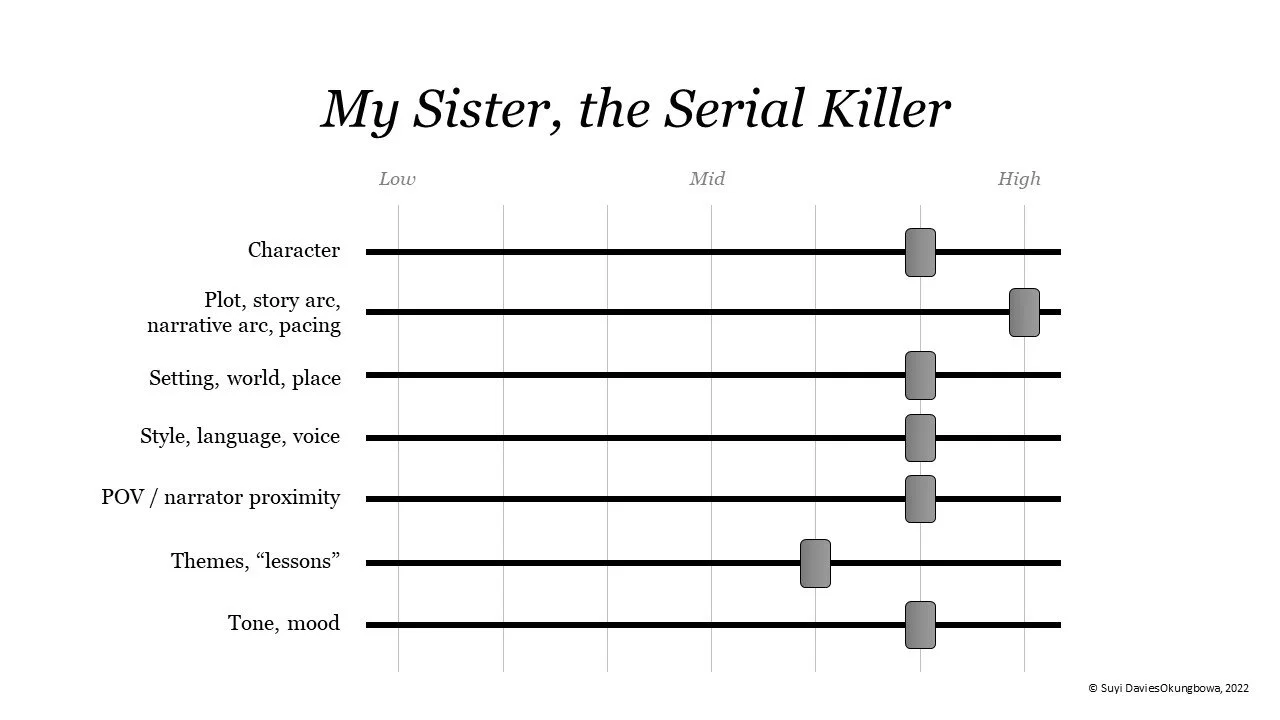

My Sister the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite, Psychological Thriller

Often, this means the thrill being delivered is less about physical violence and/or the survival of it, but about a deeper psychological issue, mostly driven by secrets and the unveiling of them. These books tend to be quite pacy but with a strong character focus regardless. I would also argue that this book leans a lot towards upmarket-y, because it also places a strong emphasis on its use of language (making it, in my head, a psychological-crime-thriller-mystery-literary novel).

Leviathan Wakes (and the novels of The Expanse) by James S. A. Corey, Space Opera

Space operas are the subset of science fiction that feature far-flung, galaxy-spanning events in worlds beyond earth’s solar system. Actually they’re a bit more than that, but that’s an easy explanation. The novels (and TV show) of The Expanse are even less space opera-y because they don’t quite feature life beyond our solar system (not until much later in the series, and even then, it’s debatable if what is featured can be described as containing “life,” but I digress). However, Leviathan Wakes, the first novel in the series, is special because it is not just a sci-fi novel, but sort of a multigenre sci-fi-mystery-horror. The novel’s quest is really a search for answers, and the answers found are mind bogglingly horrific (though more in the realm of creepy/weird than repulsive).

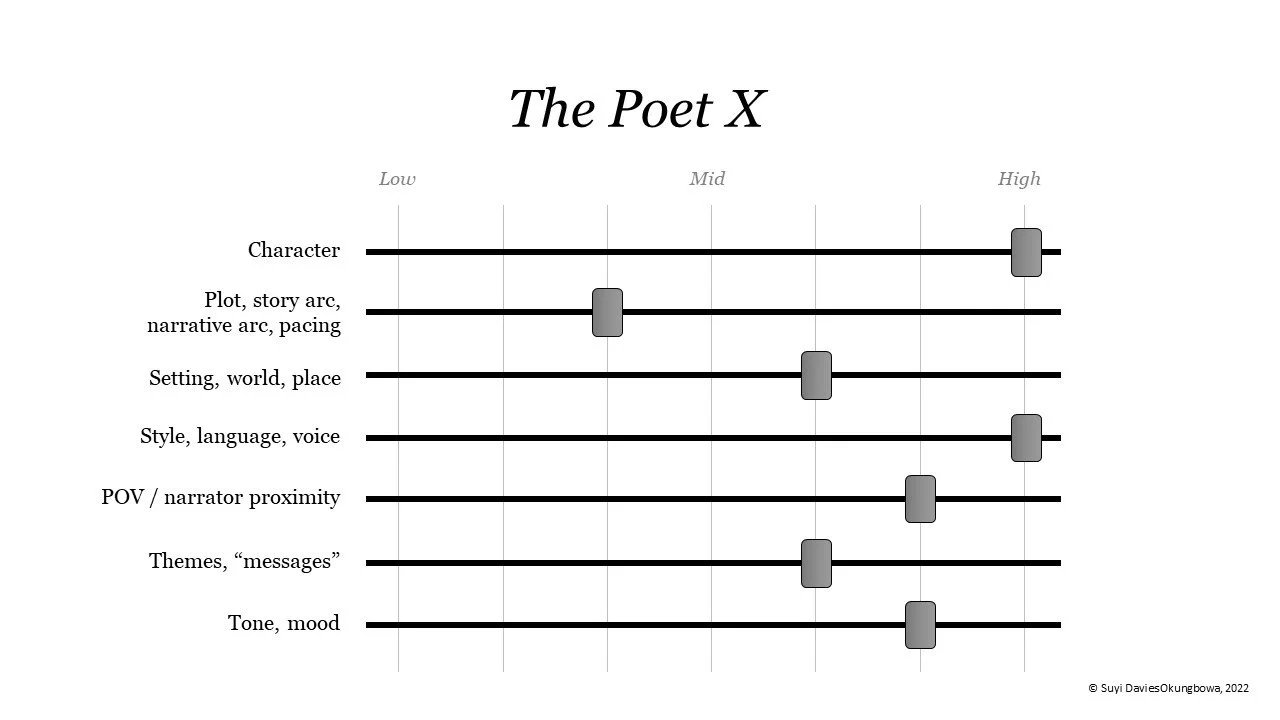

The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo, Novel-in-Verse

This is a novel told in poetic verse rather than in prose, which makes it top-level hybridity (with poetry) as opposed to a subgenre of fiction. If I was hard-pressed to locate a fiction genre this is closest to, I’d pinpoint the “literary” blend (due to its favoring of style/language/voice in a similar manner that poetry does), but this particular novel delivers a bit more than that.

Last word

If there is one thing readers take away from this lengthy piece, I hope it’s this: genres are cool and flexible and malleable. They are informed by authorial choice and authoritative repetition, then reinforced by historical dominance and ensuing audience expectation. While these labels—and the study of them—may often be eschewed by those who consider themselves purveyors of loftier art, I believe that those who wish to shape stories would consider it worthwhile to have a foundational understanding of fiction genres and how they have always moved in the world. My hope is that this piece manages to offer a way to think about just that.