On fiction genres and the elements that power them: Part 1

Photo by Hudson Hintze on Unsplash

In recent conversations with my fiction students about genres, I’ve been trying to understand how they come to know what the various genres of fiction are, or at least, how they come to recognize and perceive a work of fiction as falling within a certain category. What I’ve found is that mostly, they follow signposts in the work that tell them what kind of genre they’re consuming—whether that comes in the form of “vibes” or “tropes” or “aesthetics.” Otherwise, they simply expect to be told what (sub)genre a story belongs to by the author or publisher or bookseller or streaming platform.

But my most important takeaway from this discussion was that even though most were active readers, writers and scholars of fiction, none of their knowledge came from within the four corners of a classroom. Instead, in the same way one learns about memes or the Bermuda Triangle—via the four corners of books and screens—they had to piece it together over time.

It got me wondering why something so foundational to our understanding of fiction would be mostly absent from storytelling curricula—from elementary school to the tertiary level. Especially because this doesn’t quite happen in the same way in nonfiction and poetry, or even other creative arts: visual, performance, hybrid.

So, as I’m wont to do, I raised a question on Twitter.

The responses to my inquiry confirmed what I’d thought: many writing curricula at all levels consider it trivial (or too “low-brow”) to unpack fiction genres. They struggle to help students of fiction gain a critical understanding of each genre, understand how these stories are shaped, what elements of fiction most power them, and on the whole, clearly articulate what makes a genre of fiction what it is.

So in this piece—and in my future advanced fiction classes—I’m going to attempt to do just that. Buckle in.

Genres and elements of fiction

Let’s start by asking ourselves what a “genre” is. We could sit here all day long and unpack that word, but for the purpose of this exercise, let’s say genres are the different forms fiction can take. Call this what you wish: categories, (sub)divisions, types, styles, etc. We could also get into whether it is publishers or writers/artists/creators who decide on each genre, but that is also discourse for another time and place.

Aside 1: Notice I say “story” a lot. Though this piece uses literature as the lens through which we’re viewing genre, there is often a crossover of sensibilities with audio and visual storytelling like podcasts, TV shows, movies, etc. Examples will draw from all of these sources.

For now, we have a bigger question in hand: What makes one genre different from the other? This is where the elements of fiction come in. I’m talking about character, plot or narrative/story arc, setting/world, point-of-view, theme, voice, mood, tone, style, structure/form, conflict, pacing, etc.

The differences between genres arise when specific elements of fiction are favored over others. Those recognisable signposts we talked about earlier? They happen as a result of us deciding which elements will be the “heightened” (i.e. will be the drivers or engines of our stories) or “diminished” (i.e. not paid significant attention to), and then making choices to implement as we see fit. This produces a specific storytelling experience we can often recognize, and after much repetition, may even begin to expect. We think of these repeatable and recognizable patterns as tropes.

Aside 2: Many have argued that tropes are what make a genre. While that’s not quite incorrect, it’s not the full picture either. Tropes are simply a manifestation of the aforementioned elemental favoring. When you have a stock character in a genre—e.g. the grumpy old wizard in fantasy or the wicked stepmother in fables—it is a manifestation of the character element. When the grumpy old wizard selects a hapless farm boy to mentor and make a hero out of, or the wicked stepmother bullies the young, helpless orphan, these are plot/story arc/narrative arc elements. It is when these elemental choices are repeatedly employed by various storytellers that they become tropes.

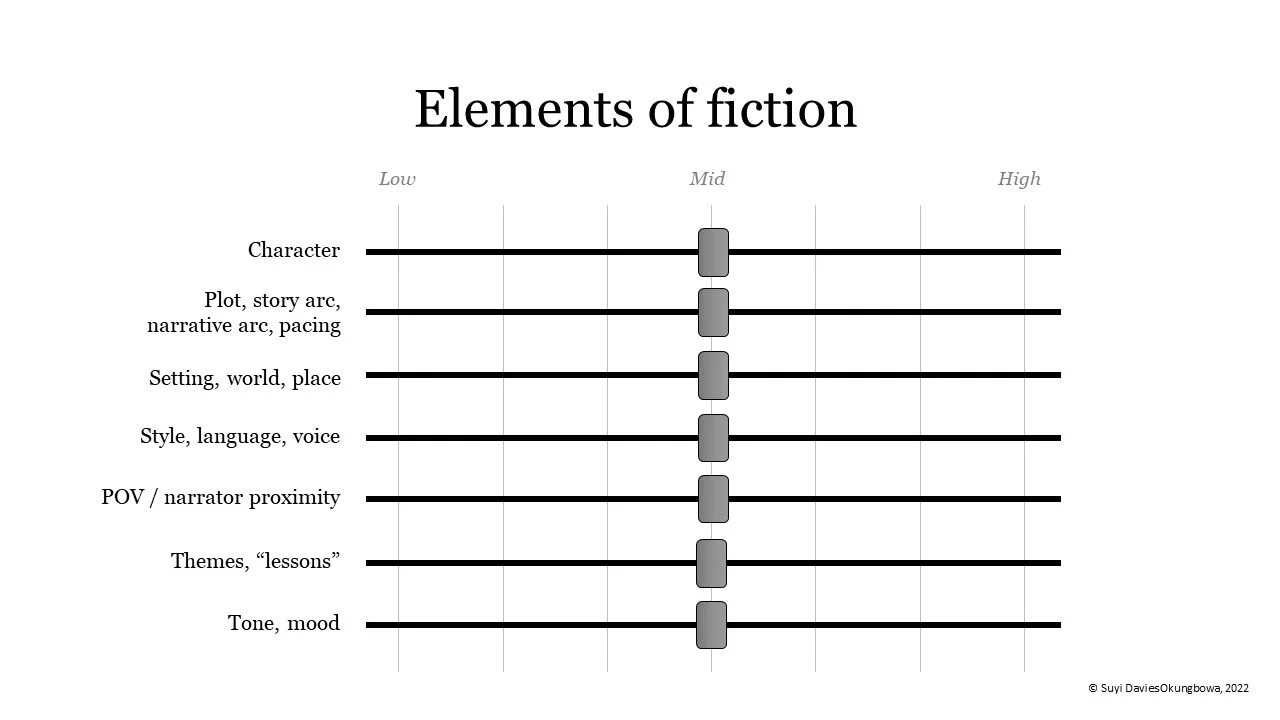

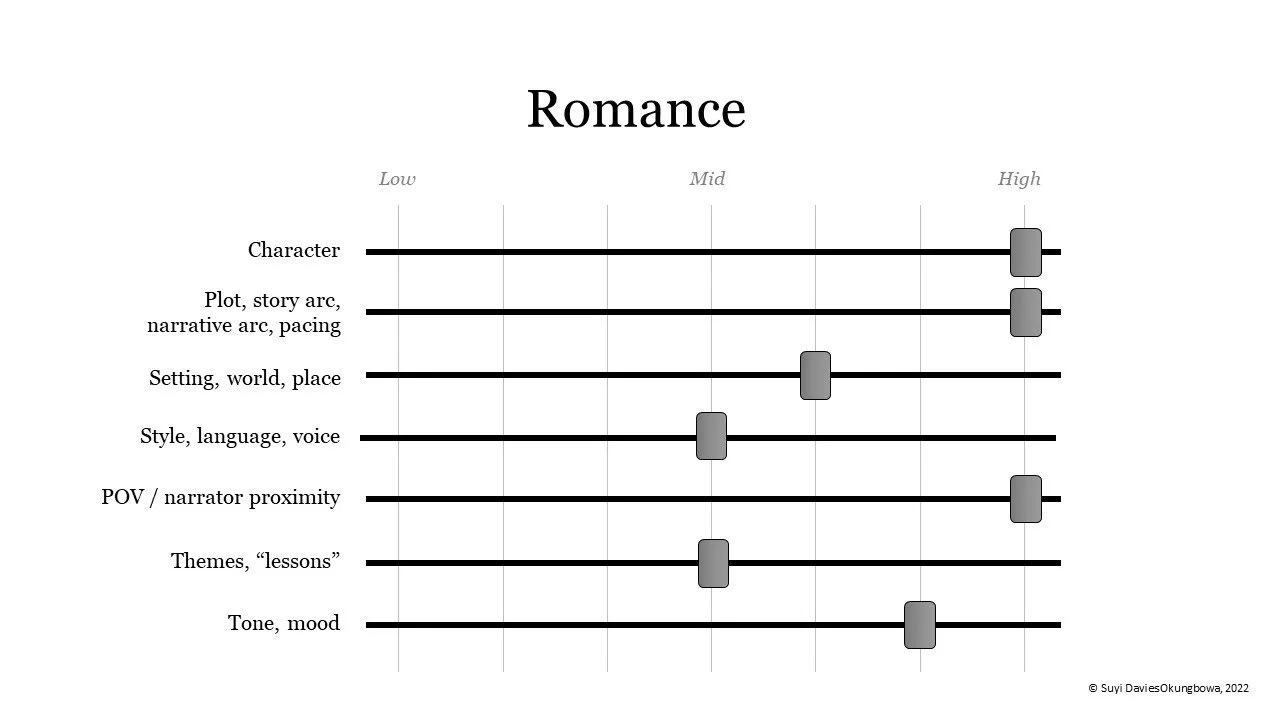

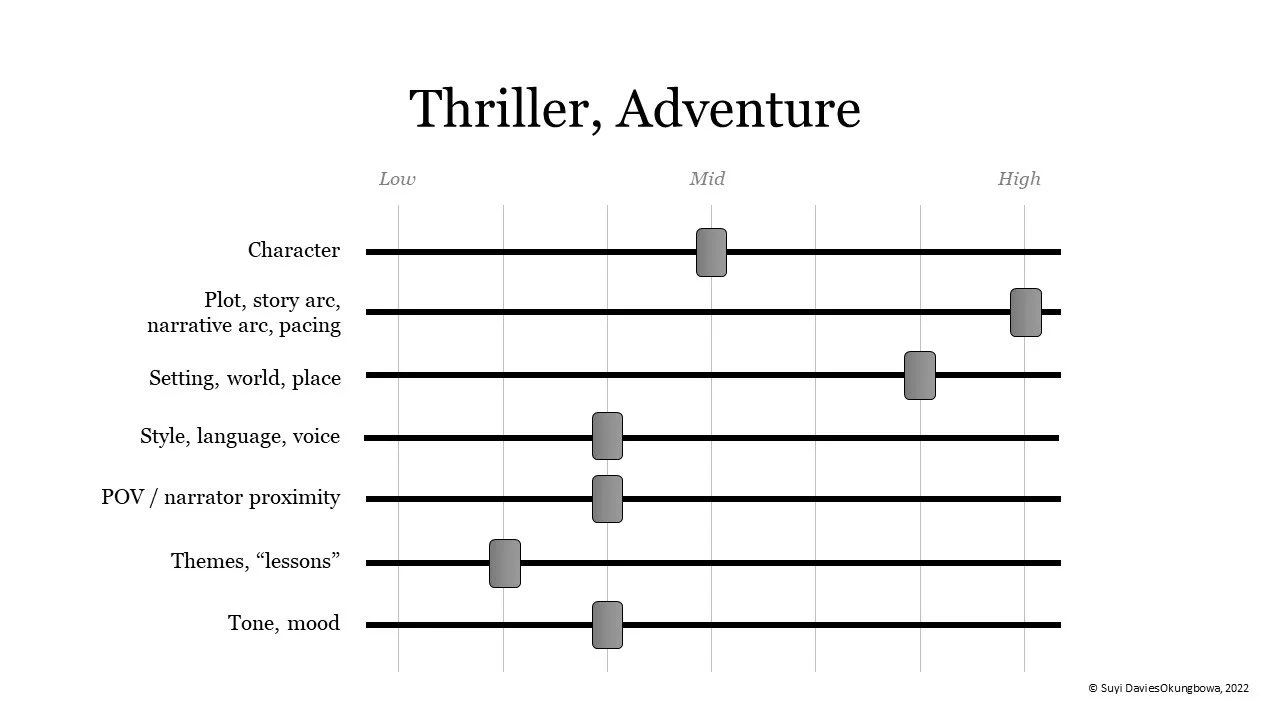

When I think of the heightening and diminishing of these elements, I like to imagine them as sliders that we push up or down (or forward and backward) depending on which elements we want to become drivers of the work, and which elements we’d prefer to take a back seat. Something like this:

Here’s my quick explanation for why I’ve grouped these elements of fiction this way:

Character: The centerpiece of most (but not all) fiction storytelling, so it stands alone.

Plot, story arc, narrative arc, pacing: Plot, story arc, narrative arc, etc are mostly interchangeable (though we could go into the nitty-gritty and say that story arc and narrative aren’t necessarily the same thing, and both are kinda different from plot if you look at it sideways, but that’s a later topic). Pacing is how we present events, and how quickly or slowly those events move on the page. I’ve grouped it here because it is a direct descendant of plot and story structure.

Setting, world, place: All pretty much same thing, though interpreted differently between genres, as we’ll come to see.

Style, language, voice: Style has to do with the writing itself (i.e. choice of words, sentence manner and lengths etc) while voice stems from the narration or character. Language sits somewhere between both. Overall, they all exist in the same ecosystem of “lexicon and vocabulary choices,” hence the grouping.

POV/narrator proximity: Basically, this is a question of “How important is the reader’s closeness or farness from the narrating entity to how the storytelling is experienced?” Often, this makes little difference outside of suitability for the story in question, but as you’ll come to see, it carries some weight in certain genres.

Themes, “lessons”: Some genres are more keen on putting forward some manner of message. Some are not about that life.

Tone, mood: Tone would tend to fit in well with style/language/voice, but I kept it separate and paired it with mood because both are specifically dedicated to shaping the reader’s experience, what we think of as “vibes.”. In some genres, this matters little. In others, the specific “vibes” must be there for readers to enjoy (and recognize) the story.

Aside 3, Disclaimer: Note that the sliders as presented below do not represent all manifestations of the genres in question. Rather, they represent a sort of average—a median if you will—of how dominant global readership tends to perceive work in that genre. Consider a slider moved toward “low” to be a diminished element, and a slider moved toward “high” to be a heightened one. Elements closer to “mid” are those that could move in either direction depending on authorial choices. Also, note that not all elements of fiction are represented here (e.g. conflict is conspicuously absent because, whether internal or external, I consider it to be a universally heightened attribute across genres). As a general rule, consider that your mileage may vary. Feel free to deviate in thinking and practice. My word ain’t Gospel.

Now that we understand this, let us peek into how these elements manifest in ten genres.

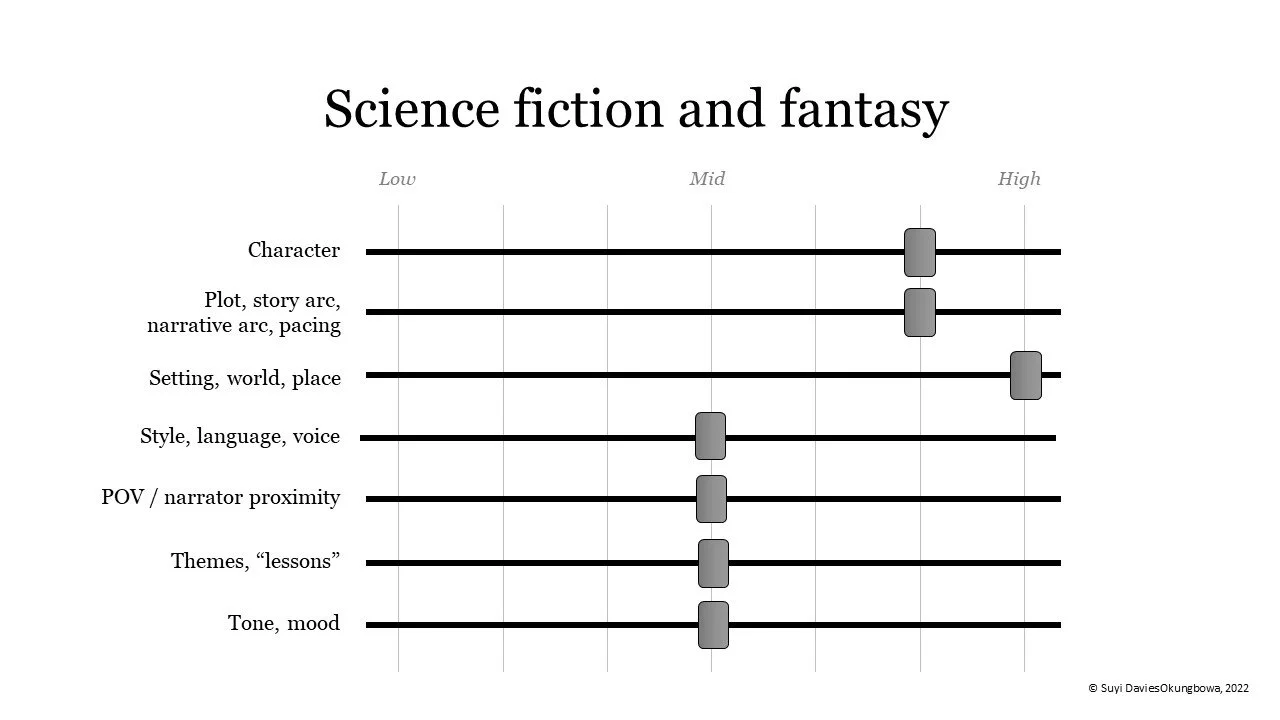

1. Science Fiction and Fantasy

Let’s start with my favorite genres, why don’t we? These two could arguably be separate genres, but we won’t get into that here. Rather, our focus is on what sets these apart, and that is the matter of speculation: the What If-ness of them. Often, this leads to the creation of new story worlds to sustain this speculation. Here’s what the average demonstration of that looks like:

It’s always been obvious that science fiction and fantasy are strongly place- or idea-driven genres, but what’s more important is that other elements require this story world in order to function correctly. Character attributes and conflict, for instance, are often driven by the story world they inhabit. Readers have also, over time, come to expect science fiction and fantasy stories to be swiftly paced, with a fascinating plot and (oftentimes) a large time-and-space-spanning arc. This is why we see these two elements—character and plot—heightened.

The remaining elements could go either way, really, depending on the author. A deep focus on language, style and voice could be significantly scaled up (e.g. authors like Sofia Samatar, Kazuo Ishiguro, Ben Okri, Emily St John Mandel, etc) or dialed down (e.g. authors like Brandon Sanderson). POV approaches also vary, with some authors preferring a bird’s-eye-view-type approach, and others a closer (see the styles in older epic fantasy versus, say the YA first-person-present styles codified by The Hunger Games, Divergent and the likes). In today’s more socially aware SF&F, themes & messages tend to stand out, but that isn’t always the case (and historically hasn’t always been). And lastly, some subgenres may have a very specific tone and/or mood (e.g. grimdark, hopepunk), while others may be ambivalent.

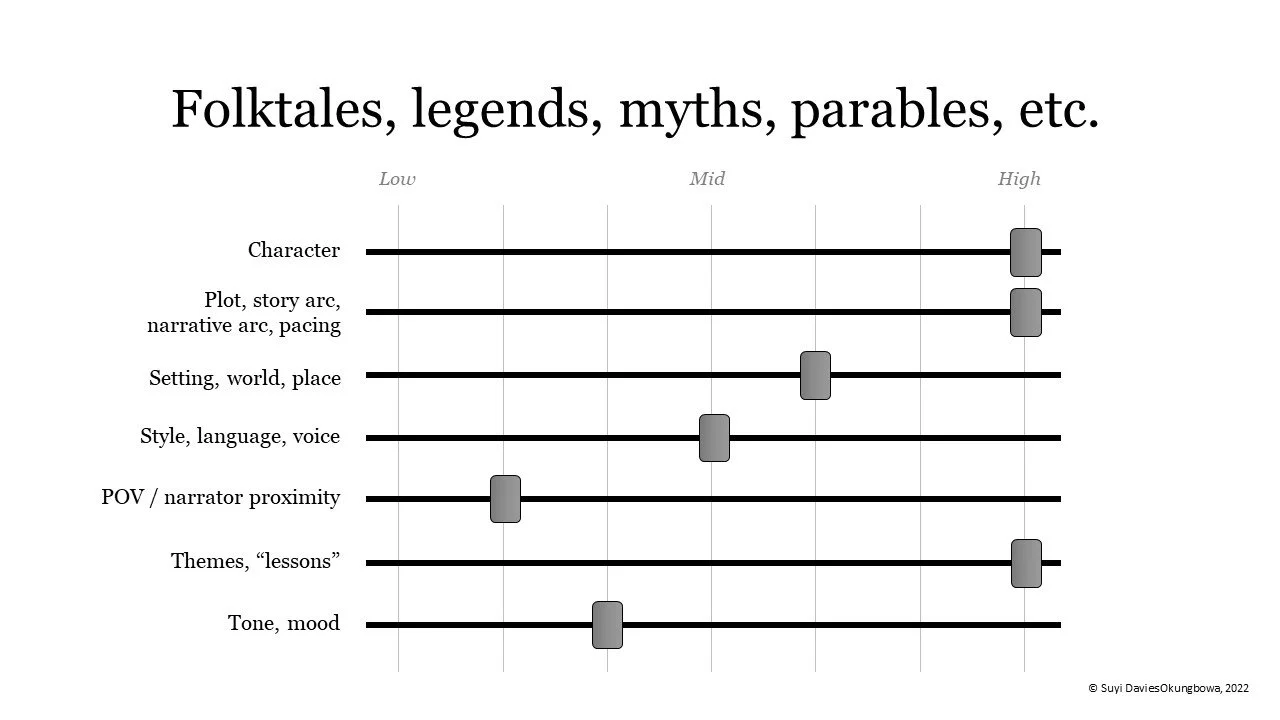

2. Folktales, legends, myths, parables

I placed this next because many stories of this sort tend to be fantastic in nature, mostly out of necessity. However, they have a different disposition from typical science fiction and fantasy because they often carry a moral burden. Their aim is typically to educate and moralize, and therefore the themes and lessons contained within them are paramount to the storytelling approach and experience.

Here, we can see that the character, the story arc and the themes are bound tightly together, as they must function cohesively to pass the message across. Whether we’re looking at Hansel and Gretel, epics like Sundiata and Gilgamesh, or Jesus of Nazareth, these stories have clear central characters, a firm plot with the aim of delivering a message at the end.

Proximity to the narrator often takes a backseat in such tales because they’re often reported stories, often told in third person by a separate entity—griot, bard, scribe, etc. This third-person narrator often ends up shaping the language, as well as tone & mood of the story, so that could vary widely. Setting could go either way, but it tends to feature prominently, even though not always as the centerpiece.

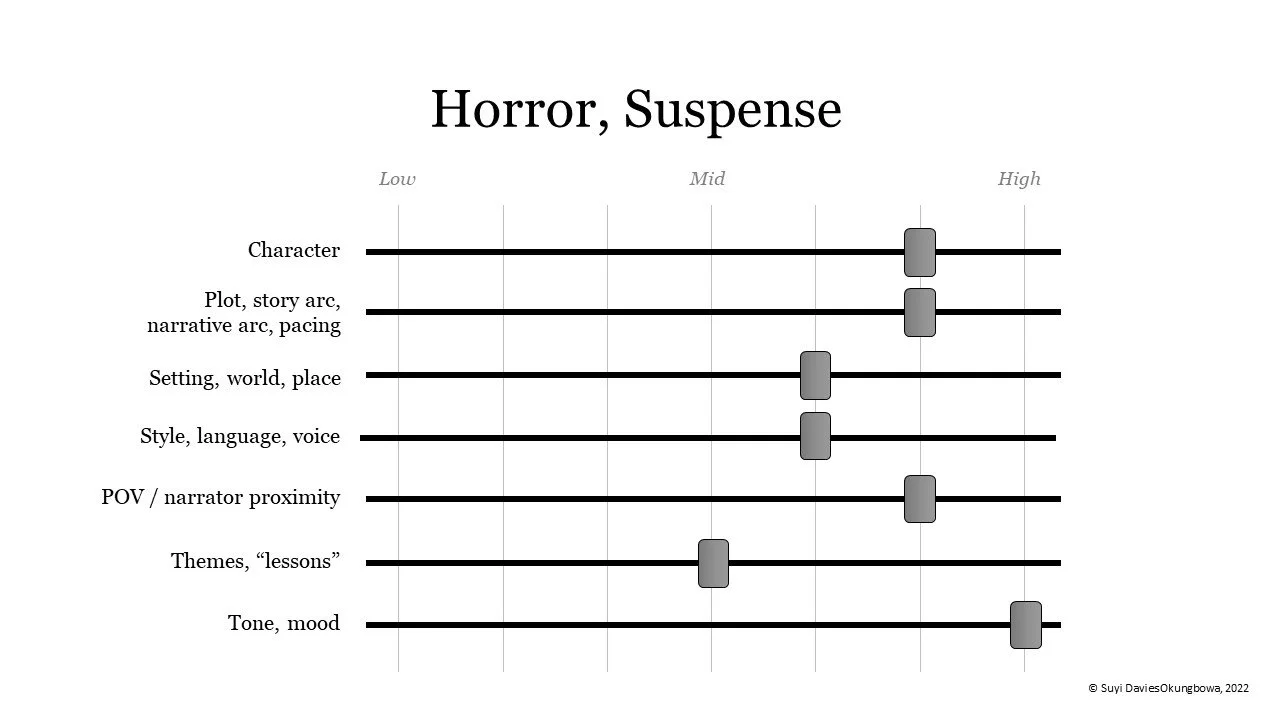

3. Horror (and Suspense)

I often don’t think of horror as a genre per se, because horror exists across a spectrum—psychological, supernatural, social, technological, cosmic, etc. What I believe sets horror apart is its use of mood & tone to evoke a response from the reader/viewer. Horror greatly depends on atmospheric, visual and psychological cues to shape the user’s experience of the story—because for horror, it is not quite about the events in the narrative, but about what the audience/readers and characters believe the events are, and how they respond to them. Most of this it inherits from its predecessor, the Gothic.

I file Suspense under this category too, because not only is it not quite a genre itself, it also takes a similar approach by driving audience and character perception. The difference between Horror and Suspense, I think, is that Suspense is all about building tension without necessarily always following through, but Horror often always follows through because it needs to let us look into the darkness and feel the terror (or grossness, or weirdness, etc). Most stories will struggle to achieve this horror without an investment in building suspense (Get Out, The Shining, Jeff Vanderneer's Annihilation and Shirley Jackson all do this well, for instance) but some can be dark and suspenseful without being horrific (e.g. True Detective, Sharp Objects, Bird Box, A Quiet Place and the podcast-turned-tv-show, Homecoming)..

4. Romance

Unsurprisingly, this is another one where tone & mood tend to be heightened—just think of those TikTok book videos about “vibes,” the success of Bridgerton and the ubiquitous AO3 ship tags. Clearly, character and plot play a significant role in this genre, even more so than tone & mood. Character, because Romance is a genre with a tight focus on interpersonal relationships—the good, bad and ugly of the human condition. Plot, because Romance requires the recognizability of certain events and moments—a meet cute, escalating romantic/sexual tension, a vulnerable confession of love, etc.

One other key thing about Romance is that it requires audience/reader proximity to its lead characters. For us to identify with them and root for their success requires a deep understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. Setting/place is a tad heightened here because it tends to play a role i.e. whatever society the characters inhabit will determine how their interpersonal relationships function, which could even be a source of conflict all by itself (e.g. see contemporary LGBTQ romance novels). And lastly, style, language and voice could go either way, depending on the author.

5. Thriller, Adventure

We may file every “action” genre under this. Adrenaline is often the major driver of these kinds of stories, and mostly of the fight kind (as opposed to the fright of Horror and the flight of Suspense). The aim of such stories is to create intrigue and a heart-racing, pulse-pounding thrill. This means that the narrative arc is often designed specifically to create situations that offer the opportunity to evoke said excitement. The setting often tends to be important too—a locale often new or “foreign” to the characters, designed to give them (and us) the impression of otherworldliness or the feeling of not knowing what to do or where to go. Whether this is set in the real world or an imagined one, survival tends to be central as a character goal.

Because survival is so often key to thrillers & adventures, character depth doesn’t always need to matter for such narratives to meet their goal (except for repeating characters over multiple stories—think Reacher, Bond or Bourne). Most other elements tend to also be diminished in favor of creating these situations and scenarios that breed intrigue and deliver thrills. Any Mission Impossible or Pirates of the Caribbean story falls under this category, as well as Tomb Raider and Jules Verne.

Continued in Part 2.